By John Willacy

–

Time is precious; none of us have enough of it. Training time eats into family life, work commitments, social life, study time and pretty much everything else. The trick is to get the most out of training with the least amount of time committed.

So we need to make training efficient and effective. Train hard, then get off the water and head home to get on with life until the next session.

To get the best out of training takes a little reflection and bit of application. So let’s take a look at how to make the most of our training time.

The four cornerstones of my training over the decades are:

- Industry – how much work I do

- Intensity – how hard I work in those sessions

- Quality – how I plan and review to get the best out of every activity

- Repetition – continually repeating these activities for subtle but steady long-term improvement

Each one of the four is important in its own right. However for significant and long-term performance gain, whether it be physical, technical or mental, then all four are required to be brought together.

However, before we get into the details, let’s take a slightly flippant look at a side to physical improvement – i.e. fitness gain.

The body’s Fitness Foreman (FF) sits around managing our energy reserves – balancing energy commitments required for physical activity and those required for fattening up for the next ice-age. (The FF is a climate-warming sceptic it seems). When, out of the blue, we suddenly go for a jog or jump on the bike, or even go for a sweaty paddle- the FF is taken a little by surprise – ‘Whoa! What’s all that about?’

But then we stop, the panic is over and calm returns to the office of the Fitness Foreman. However next week we do the same thing again, the FF is worried that a pattern is forming – ‘Hey boys, better send a little more energy down to the good chaps in the Fitness Department to help us with this. They can buy a bit more Lycra or whatever they do…’

The pattern continues the following week and the FF diverts even more resources to the Fitness Department – our fitness levels improve a little and as energy is diverted to do this our bums, tums and hips get a little smaller too – the weekly jog, bike, paddle etc. seems a touch easier too.

Eventually things balance out – the FF gets a grip on things, anticipating the weekly session, the energy the FF sends to the Fitness Department is enough to cope with our training session. Our fitness improvement plateaus, it’s higher than where we started from, but to go further we need to get the better of the FF and stress the little beggar a bit more.

Now to further improve physically we need to do one of three things with our training sessions:

- Increase the Frequency

- Increase the Intensity/Quality

- Increase the Duration

If we do this our fitness level will increase once again. Of course sooner or later we will reach another plateau, and, you’ve guessed it, the cycle continues. Eventually we can’t raise things any more – family, work or our bodies won’t give any more – we’ve reached our limit.

But what happens if we don’t do this? In fact what happens if we go the other way and reduce the number of our sessions say? Of course the catch is that fitness levels will lower without work.

Well, the Fitness Foreman is quick to act, very quick unfortunately. The FF cuts down the energy going to the Fitness Department and diverts the difference back to his fixation of Ice-Age Preparation – bums, tums and hips get bigger and we get slower. Fitness levels drop – our now not-so-weekly session starts to feel a little tougher, a little less pleasant.

Ok, so what does this all mean?

Basically, regular training is going to improve our fitness levels (and, if we don’t eat too much helps us lose some weight). After each episode we have a short period of grace as our body takes the exercise stress as a prompt to improve our fitness levels in order to helps us cope better the next time the activity is repeated.

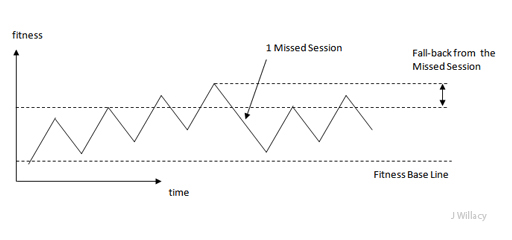

Our fitness levels are like a saw-tooth, rising and falling with periods of activity, followed by inactivity. These fitness levels peak a short time after the activity, and then our body starts to regress and fitness starts to drop steadily away from that peak. The trick to the training programme is to get the next session in before the fitness level falls back to, or below, the base-line level -where it was prior to the previous session.

If we manage this we get a steady, long-term increment in fitness. If we leave it too long before the next activity, part of the benefit from the most recent activity is lost in just bringing us back up to the base-line, any remaining benefit still goes to improving our fitness – just to a lesser amount.

So, onto the Cornerstones:

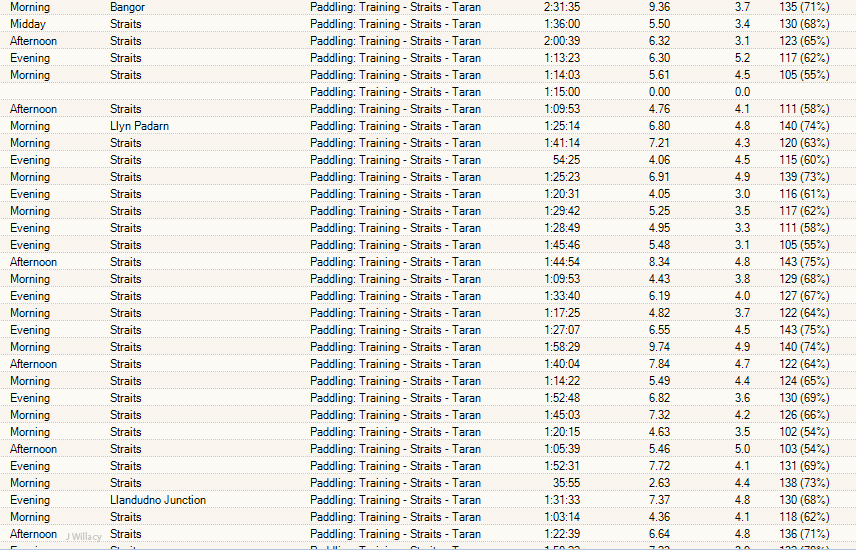

Industry

Basically how many training sessions in a training block – which can be a day, a week, month, year or whatever. Industry relates to the frequency, but more importantly, the regularity of these sessions.

It’s fairly obvious that the more we train the fitter we get, that’s not quite the full story of course but it’s a pretty good starting point – 3 sessions per week will get us fitter than 1 session per week – all things being equal. However, the often overlooked and important factor here is regularity – consistency in training. This is significant.

As we saw, a short period after we finish our activity our fitness levels start to fall back – we need to get that next session in before we return to the base line. So if we miss a session we lose fitness and we have to train just to return us to our previous level, rather than developing fitness.

How long is this interval? Well that depends on many factors, including: the type of training undertaken, training intensity, each individual and the current fitness level of the individual. Rather ironically, the highest levels of fitness drop off the quickest…

The important point here is that fitness drop off is measured in fixed finite time periods (days/weeks), and not in a ratio or percentage relating to the amount of training currently being undertaken. To illustrate this:

Paddler A trains in a boat 1 session per week, each week.

Paddler A can’t train this Wednesday because there’s something important happening in the omnibus edition of the Archers. So that’s 1 session lost, that’s all, 1 session, no great drama – but, here is the catch, that 1 session actually means 2 weeks between paddling sessions…

That 2 week gap is a long time in the world of Fitness Regression. I would suggest that a 2 week gap means a fitness drop-off equivalent to around 4-6 weeks development at 1 session per week. So missing only 1 weekly session means that Paddler A has lost perhaps between 1 to 2 months of training development, at 1 session per week. A few gaps in a season can mitigate many weeks, even months of work.

Paddler B trains 3 boat sessions per week, each week.

So if Paddler B stays home to listen to the Archers and also misses one session, but now the time lost from training is actually only 5 days at the most. This means a much lower fall-back – perhaps equivalent to between 1 and 2 weeks development.

The important point is that it is not so much the number of sessions missed as the number of non-training days between sessions.

For high-end daily training I work on a rough benchmark that 3 days missed means a fall back of 7 development days for me. Add to this the actual 3 days off and you now have lost 10 days of training development for a 3-day break.

It’s not the end of the world, life’s like that, shut happens. But it may start to explain why sometimes you just don’t seem to be getting any faster. Some form of training diary here will highlight just how regular your training actually is.

If you know you’ve got a break coming, then squeeze a session in as late as possible before you go, and then one as soon as you get back. Minimise the number of days between sessions, and if you can fit in some form of exercise during the break to help stop the Fitness Foreman larding you up for the Ice-Age.

Industry – train frequently, but more importantly regularly. Otherwise you redo the work, again and again.

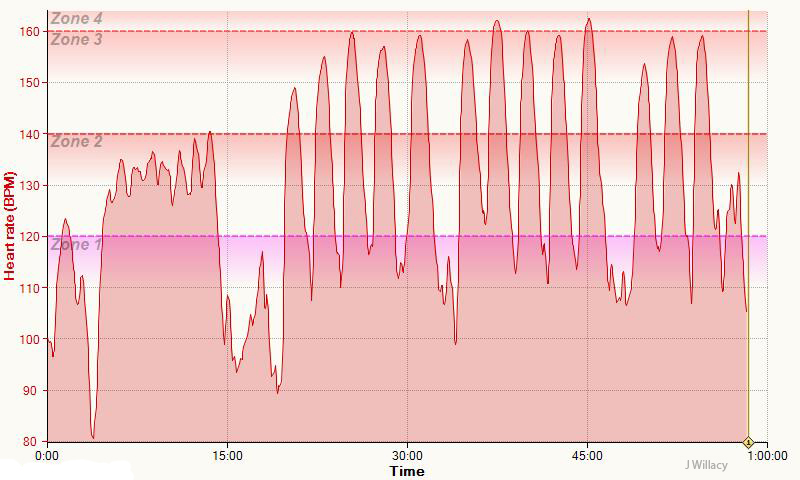

Intensity

This is how hard you train, both within sessions (micro-level) and also within training blocks (macro-level). It can be difficult to get the intensity level right – always train slowly, always race slowly. However, train too hard and over-training may head your way – fatigue, loss of training quality, de-motivation and possible injury.

The intensity needs to be correct both at the micro-level and at the macro-level for effective training.

Sessions just bimbling around chatting, with the odd sprint thrown in to make you feel better, probably are not classed as a useful intensity. Likewise neither is 60 hard sessions in a month without a rest day. That’s going to end in tears.

A good way to maximise the overall intensity is to use contrast training. For frequent training, follow hard sessions with easier ones i.e. a hard time-trial may be followed by a shorter sprint session. Also blocks of paddling sessions may be separated with cross-training – bike, swim, run, S+C (strength and conditioning) or whatever. Try to alternate different types of training and different intensities of training. Hard day – Easy day.

This principle also works at the micro-level within sessions – a hard session of 6 minute efforts say could be finished off with a number of 15 second sprints perhaps, and these would likely still be worthwhile – contrasting different body ‘systems’..

Intensity – Train hard, but balance this with rest and lower-intensity work.

Train slowly – race slowly. Train too hard and things will go bang.

Quality

Plan and Review

Every session should have an aim or goal, as should every training block (day, week, month or year) and likewise every activity within a session should have an aim or goal too.

At the end of each activity, session or block, performance should be reviewed to ascertain if the goal was achieved, and to see what action is needed to correct or improve further this performance.

Now that may sound a little deep, but it is not that bad. Yes, some may sit down every Sunday night (usually in the racing world) and write-down what they achieved in the last week, how they can improve on it and what they are going to do in the next week – specific goals and aims. Phew!

For others it may just be as simple as, ‘well that was a crap week, need to make sure I get down to the club on Wednesday instead of listening to the Archers again.’

In a session:

Session Goal – ‘I’m going to practice my ferry glides tonight.’

Activity Goal – ‘I’m going to cross the flow and finish by the old tree on this effort.’

Activity Review – ‘How did it go? Well I dropped a little low, so next run I need to point the bow further upstream before crossing the eddy line’.

Activity Goal – ‘I’m going to cross the flow and finish by the old tree again’.

Activity Review – ‘How did it go? Yep, that better angle worked, I finished where I wanted to’.

Session Review – ‘Yes, practiced the ferry glides, did 10 with 7 good ones. Learnt not to leave the eddy with too little angle. Remember this for next time. Pleased that my ferry glides improved through the session. Job done – let’s go home’.

Plan and Review – for some it may mean time spent in written consideration, for others it is no more than a few seconds of mental self-questioning and encouragement. It becomes easier and should eventually become common place for everything you do.

Analyse

Think things through. Ask yourself questions and think through to the answer. Don’t wait for others to tell you how or what to do. Take responsibility and work it out yourself – you will learn so much more. It’s important for the long term.

Discipline

…is necessary here too. Make sure you achieve what you set out to do – exactly. Nearly is not good enough – make it happen and do not sit back until it does.

If you accept slalom gate penalties in training, then why are you surprised when you get them in racing?

If you always let the boat eddy out before the shore in ferry glide practice, then why are you frustrated when it won’t go into the eddy when you need it for real in the big tide race? There is a pattern here… Standards in training equate to standards in racing.

Focus

Spraydeck on, session starts… Keep a focus throughout your session – save the chatting for the before and after (or social paddles).

Make time for chat outside of training, waffling on at length while on the water – about work, the Archers or life in general does not help with the job in hand. Once the talking starts, paddling intensity drops, mistakes creep in (What? Aah, that rock! Oops.), mental and physical warm-up suffers, focus and quality trickle away. Time is wasted.

Quality – plan and review, analyse, discipline, focus.

Repetition

All of the previous cornerstones are linked to this one – Repetition.

Practice makes perfect so the saying goes. Or perhaps for some, more sceptically, practice makes permanent. If you have an eye for quality in your training it should be the first one, there is no reason why not.

The modern ‘instant-fix’ world is a little at sorts with the mechanics of long-term training and development. Long-term improvement doesn’t happen overnight, the clue’s in the title. There are no short-cuts here. Let’s say that again – there are no short-cuts.

A skill can be learnt in an afternoon, but it may take a lifetime to master it…

It takes a long time to get good at paddling and as you get better, more skilful and fitter it takes even more work to move up to the next level. The pain-in-the-arse law of diminishing returns comes into play. To get seriously good at something – the difference between the good and the very good, takes not just weeks or months, but years of regular, quality repetition. Think about that one.

So our training is formed around this endless repetition – to improve our skills and technical ability, to improve our fitness and familiarise us with countless varied situations.

While we can see the need for repetition to improve our skills and fitness we also need to understand the value of familiarisation. Just spending time in the boat helps us improve our skills and fitness sub-consciously – passive development, rather than the active development that comes from the specific Plan and Review approach of sessions.

The more times we cross a start line the better adjusted we become to race-day nerves…

The more we paddle, the more fluid our forward stroke becomes…

Somehow, the more times we paddle open-water, the better we just seem to get at running the boat down-wind or cross-sea…

Strange that…

We don’t get this passive development from watching YouTube videos, or even reading books (Youngsters, ask mum or Dad about them…) – To be a good paddler you need to get in a boat. A lot.

Go paddling. Once you’ve been paddling… go again.

But doesn’t all this repetition get boring? Not if you have an imagination, are prepared to analyse and reflect, and are constantly looking for improvement. Every time.

Repetition allows us to experiment. We can try different methods and approaches, and learn from them. If we repeat more than the other guy, we can try more different methods than they do. We will learn more.

No matter what they tell you about learning styles, as a paddler there is no better way to improve than to be out in a boat and just trying things…

Repetition – Go paddling. Try things out. Once you’ve been paddling… go again.

So:

Industry – Frequent and Regular – Regular is more important

Intensity – Work hard, Rest hard.

Quality – Plan and Review, Analyse, Focus, Discipline.

Repetition – It never ends

John Willacy

Oct 2016